18F and Medicaid

1 July 2025

In the beginning

In 2016, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) reached out to 18F. They wanted to help the states more successfully implement their Medicaid Management Information Systems (MMIS). These are extraordinarily expensive software systems that handle paying medical providers for work they do for Medicaid members. And many of them were the same systems that states had built in the 1980s.

CMS was aware that state MMIS modernizations were failing, costing a lot of money, and jeopardizing good healthcare outcomes for people in need. As part of the Affordable Care Act, Congress has authorized the federal government to reimburse states up to 90% of the cost of their MMIS modernizations, and CMS was trying to put rules in place to encourage good outcomes and lower costs. They were on the right track, but states were struggling to figure out how to implement new systems.

CMS picked five states for us to partner with. The goal was fairly simple: identify roadblocks to states' success and help them overcome them. With each state, we spent a few weeks reading through all of the documentation they could send us about their existing systems, past or ongoing modernization efforts, contracts, state budget rules, org charts, and... well, really, anything they would send us. We'd also have meetings with various state and vendor staff to refine our understanding of the current state of play. Then we held on-site workshops with each state, establishing a shared understanding of the "as-is" system, a vision for the "to-be" system, and coaching on product ownership, user research, and what we called "modular procurement."

And we oop

We quickly realized that we'd stepped straight into the deep end of the Medicaid IT pool and were in way over our heads. Our state partners understood what they needed to do, but they didn't know how to get there. And quite frankly, our advice wasn't going to help them because some of the biggest hurdles were coming from inside the house, as it were. CMS's new rules for how to build Medicaid IT systems were nigh impossible to implement. For example, CMS wanted states to focus on "modularity," or breaking their Medicaid IT systems into discrete pieces that could be built independently. The goal was to allow states to move more quickly and, hopefully, share modules between each other. In practice, however, states couldn't figure out how to break their systems down, and honestly, neither could we.

But this wasn't actually the first CMS-imposed roadblock we noticed. Instead, we kept hearing about Advance Planning Documents (APD). APDs are documents that state Medicaid offices write to request funding from CMS for building IT systems, and these were some gigantic documents. States often spent several months preparing them. The documents had to explain the state's project management approach, what modules it planned to build, how much it expected each one to cost, how those costs were to be allocated (e.g., how much was paying for state employee costs, how much for contracts, how much for travel, etc.), and detailed timelines. Right on its face, the APD process denied states the opportunity to be agile and responsive as CMS was demanding.

Worse, the APDs were so information-dense that CMS's state officers – the people who reviewed and approved the funding requests – needed weeks to months to review and respond to them. And the documents often contained errors, not least because the budgetary math was so complex and state officers were required to send the APDs back if anything was off by even $1. This back-and-forth resulted in very long times between when a state requested money and when the money was actually delivered.

Course correction

By mid-2017, we realized that states could not successfully adopt a more iterative and flexible approach to building IT systems with the APD process as it was. We also realized that MMISes were extremely complex and probably not the right place for us, CMS, or states to be figuring out how to work in this new way. As a result, we changed course in two distinct ways: first, we suggested to CMS that we should instead work on the more narrowly-scoped Eligibility and Enrollment (E&E) Medicaid systems; second, we suggested that CMS let us research the APD process from the ground up and see if there might be a better way to meet the statutory and regulatory requirements they are meant to serve.

CMS agreed with us on both fronts. From 2017 until early 2020, we worked directly with a handful of states on modernizing their Medicaid E&E systems. These bore fruit, though they were still hampered by APDs and other CMS requirements.

Looking at APDs

Meanwhile, we stood up a new team to tackle APDs. This consisted of a metric ton of interviews with CMS state officers and state Medicaid and acquisitions professionals. We needed to understand who the APD was meant to serve and how. We assumed it was entirely for the benefit of CMS, but we quickly learned that states also used the APDs for their own purposes, including submitting them to their state legislatures for oversight and budget purposes. We also needed to know which parts of the APD were truly useful; which parts were not; which parts were difficult; and who those parts were useful, not, and difficult for.

What we found was that states weren't sure what CMS wanted in the APDs, so they put in everything they thought might be relevant. One state even included a history of the state seal! CMS state officers, meanwhile, lamented the amount of unhelpful information in APDs, such as histories of state seals. All parties agreed that having a clear template for what should be in an APD would be helpful. They also agreed that the budget math was too difficult to get right and it would be super if CMS provided a tool for computing it.

At the end of our research period, we recommended to CMS that they build an interactive web form for creating APDs. Our argument was that this provided a way for CMS to clearly specify what information they wanted, to impose limitations on that information (such as maximum word length, to prevent states from publishing whole novels in their funding requests), and to build out the complex Medicaid budget tables correctly and in realtime. We also suggested to CMS that building such an app would give them a great opportunity to distill the APD down to just that information that was actually important.

Once again, CMS agreed with us, and with the help of two very eager state officers, we were able to get approval to start building an APD web app. We dubbed it eAPD. While the primary goal was to simplify and speed up the process of drafting, reviewing, and approving APDs, we had secondary goals as well. As we built the new application together, we were intentionally teaching our partners at CMS how to be product owners. We were showing them the value of user research, rapid iterative development, frequent releases, and regular product demos. We had a hunch that CMS state officers getting hands-on experience with the process of building software in an agile way would be wildly beneficial to them when it came time to oversee states doing the same thing.

We worked on eAPD from early 2018 to early 2020. Along the way, we held several user research sessions that helped us adjust and refine our approach, including one in which a research participant told us quite bluntly that they hated what we'd built. As evidence of how well human-centered iterative development works, however, they later stood on stage at a conference and sang eAPD's praises (after we'd addressed their concerns, of course). When 18F rolled off eAPD, CMS continued the work with a contractor, and they had the tools and expertise to oversee the vendor's work. eAPD went into production for a smaller subset of Medicaid projects called HITECH in 2021, and CMS reported that APD review times were substantially shorter.

APDs aren't the only booger

Throughout 2017 and 2018, we built great relationships with CMS leadership and staff, and we gained a ton of understanding of how Medicaid programs worked. Between our projects with states on E&E modernization and our work on eAPD, we learned a lot about the challenges of Medicaid IT, and because we had so many simultaneous projects addressing different aspects of Medicaid IT, we also started seeing relationships between pain points.

This led us to a whole body of work directly with CMS around project oversight in general. In 2019 alone, 18F and CMS:

- drafted regulatory changes to better describe CMS's oversight role, giving it more flexibility in how it engages with states and making it easier for states to meet their obligations

- partnered on another project to streamline the submission of required state data

- researched the role of state officers from the perspective of both CMS and the states they served

- developed a "Rosetta Stone" to help state officers identify when projects were at risk so they could intervene sooner

- created a high-level Medicaid IT systems map

But that was just 2019, and the work continued. Together, we developed a Medicaid Enterprise Systems (MES) health tracker so CMS had a better sense of how Medicaid modernization was progressing at all times. We also built and ran a training curriculum for state officers. This was geared towards teaching them product ownership skills – similar to what we were doing with eAPD, but this time more abstract, since the state officers were not actively building anything. Still, we believed that those skills would help them more effectively identify risks in state project plans. The training also focused on "good" questions to ask states as the work went along, based on what we had seen firsthand with states that were struggling.

Perhaps the single biggest piece of work in 2020 was a service design workstream we led to get everyone in the Medicaid ecosystem on the same page about the longterm vision for Medicaid IT. CMS, states, and the vendor community all participated and helped draft a clean and concise view of the future.

We continued this stream of oversight work into 2021. One of the problems we had identify early on was that CMS seemed to have competing priorities. The service design workstream had helped to smooth those out, but the risk that priorities would diverge again was quite high. Together, we built an MES Alignment Toolkit, which served as a way for CMS to keep their priorities together across different oversight projects and across time.

Additionally, we kicked off a research project to understand why Medicaid IT contracts were terminated. CMS knew that contracts were terminated frequently, and often without cause. These terminations are expensive – the money already spent is lost, and the projects have to start the process anew. They wanted to know why it was happening. 18F interviewed a bunch of CMS state officers, state Medicaid staff, and Medicaid contractors to discuss failed contracts and why they ended the way they did. Our final report outlines our findings and recommendations, and this is one of the finest research reports 18F ever produced.

One thing our final report doesn't mention is a perverse incentive that states have to terminate contracts for convenience. If a state terminates for cause and attempts to recover money from the vendor, CMS will then expect its portion of that money returned as well. Since CMS foots up to 90% of the bill, that could mean the state spends far more money in litigation than it will ultimately get back. For example, if the state recovered $10 million, they might immediately owe $9 million back to CMS, meaning the state only recovers $1 million. If litigation takes years, they will have spent far more than that in legal costs, so it hardly seems worthwhile. We wondered if CMS ought to impose contract language that allowed CMS to recover funds itself, but we decided not to go that route for fear of scaring the vendor community.

Where we landed

The year 2021 was tumultuous for 18F, and political leadership above us stopped all our work with CMS – against our will and against CMS's. The end of our years-long relationship gave us time to reflect on what we'd accomplished together. That was heartening, while also being extremely frustrating given how close we were to tying up the loose ends we'd left behind in 2016.

By the end of 2021, eAPD was helping states submit funding requests with just the right amount of information and correct budgetary math while simultaneously speeding up the review and approval process on the CMS side. This directly addressed a serious hurdle we found way back in 2016, which was the agonizingly slow process of getting the money-spigots turned on. CMS also had an excellent training curriculum for helping its state officers review and monitor state projects, and it has tools for maintaining a coherent set of priorities. Finally, CMS, the states, and the Medicaid vendor community have a set of recommendations to help each work towards better Medicaid IT outcomes.

All of those things were areas of immense friction we'd identified in 2016. And in those intervening years, 18F had learned a LOT about Medicaid. Not only had we worked with CMS to alleviate some of the burden it placed on states, but we'd also worked with states and vendors directly to build E&E systems, strengthening the states' product ownership muscles and empowering them to deliver better results. We were finally ready to dip our toes back into the MMIS modernization we'd started with.

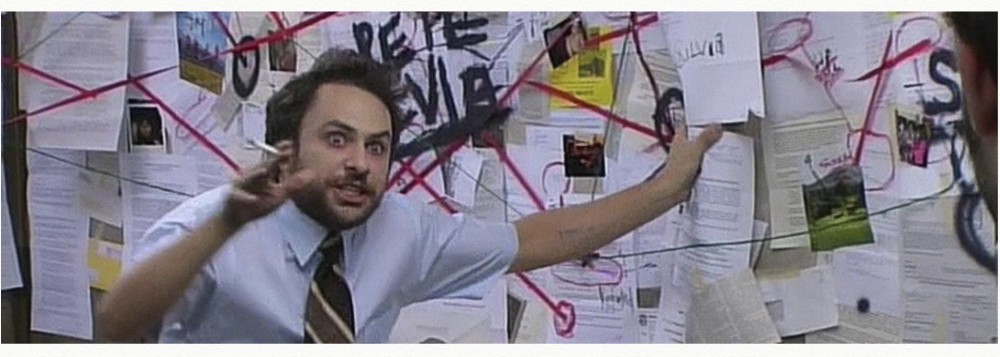

Here's a timeline document showing 18F's work with CMS and states from 2016 through 2021, and how all those pieces of work related to each other. This was an informal timeline I put together when our political leadership terminated all our work with CMS, because I needed to see it laid out to validate my belief that we were close to a major breakthrough.

Conclusion

Government work is not fast. It's not supposed to be. The interconnections between various systems and stakeholders are vast, and they have to be navigated with great care. They also cannot be dissolved – it's a spider web, and plucking one string will vibrate all the others. It's important to understand how a change in one place will ripple throughout the system.

But you also can't wait until you form a perfect understanding, or you'll never get started. So you have to look around until you find something that looks small enough not to be too disruptive. Find a small thing that everything else depends on but which does not depend on anything else, or the other way around. The smallest pond, where tossing in a pebble produces the fewest ripples. And you toss your pebbles into that pond.

It takes a lot of patience to unwind all the pieces and parts that go into a government service. It takes a lot of humility to recognize and accept that all those parts exist for a reason. You can't just throw them away. You may be able to replace them, but you'll need to do it with care. You have to understand what need they address.

It's not fast work.

But when it's done well, it's beautiful. Done carefully, you save billions of dollars and provide better outcomes to the people the government serves. That's the government we deserve.

suddenlygreg.com » 18F and Medicaid

suddenlygreg.com » 18F and Medicaid